|

On the evening of Sunday,

June 24, 1973, James “Jim” Massacci, Sr.

was relaxing at home with his family

when a call came in from his bar, The

Jimani, located at the corner of

Iberville and Chartres Streets in the

French Quarter. The employee on the

other end of the line told Massacci that

smoke was coming from the windows of

another lounge upstairs from the Jimani,

and that the police and fire department

had been called. Although it didn’t

sound like much of an emergency,

Massacci decided to head down to the bar

anyway, just to check things out; he

brought his young son along.

A few hours later,

Massacci and his son, twelve-year-old

Jimmy, were standing by in horror,

surveying the remnants of one of the

most gruesome and tragic events in the

history of modern New Orleans. And on

that night they became members of a very

exclusive club, a small group of friends

and neighbors who could say, in the

intervening years, that they were there

the night the Upstairs Lounge went out

in flames.

Upstairs Front Door with

Barred Window Next to It

But in the landscape of

1973 New Orleans, “Gay Pride” did not

exist. A handful of gay bars were

scattered around the French Quarter,

usually in derelict or crime-ridden

neighborhoods that provided secrecy in a

city where gay life was lived almost

entirely underground.

The Upstairs Lounge was

located on the second floor of a

three-story building at the corner of

Iberville and Chartres Streets. Jim

Massacci’s Jimani bar occupied (and

still occupies) the ground floor, and

the third story consisted of bare,

sparsely furnished “flop” rooms that

Upstairs patrons sometimes used for

sexual liaisons.

That Sunday, June 24th,

was the last day of national Pride

Weekend and the fourth anniversary of

the Stonewall Gay Pride Uprising of

1969. At the time, the bar was also the

temporary home of the small New Orleans

congregation of the Metropolitan

Community Church (MCC), the nation’s

first gay church that had been founded

in Los Angeles in 1969.

Worship services had been

held earlier in the day and congregation

members had stayed to join regular

patrons for an afternoon of free beer

and an all-you-can-eat special. At the

height of the activities, almost 130

people were jammed into the bar, but as

the evening wore on, and the beer ran

out, the number dwindled to

approximately 60, most of whom were MCC

members.

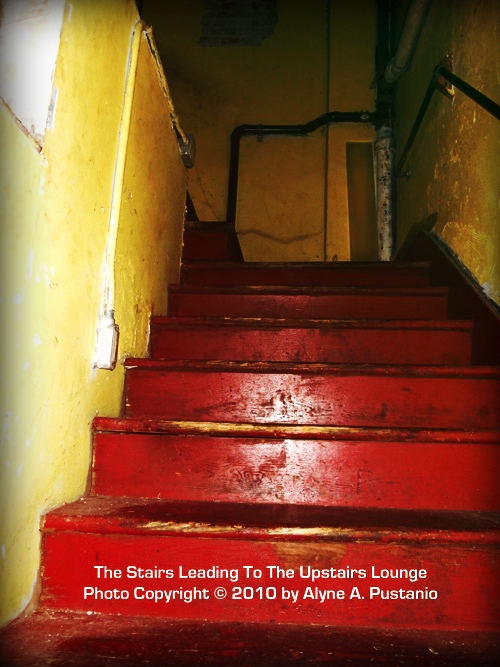

The building that housed

the Upstairs Lounge was one of a rare

few left in the French Quarter that had

a wooden exterior; the lounge had only

one entrance, up a wooden flight of

steps and a narrow hallway from a door

that opened directly onto the Iberville

Street side. The lounge consisted of

three open rooms, decorated in the plush

style popularized during the 1970’s,

with long bars and a cabaret stage

complete with a baby grand piano.

MCC members and Upstairs

regulars often gathered around the piano

for sing-a-longs; one popular song,

“United We Stand” by the Brotherhood of

Man, had become a kind of anthem for the

Upstairs crowd. One of the most popular

performers at the Upstairs was pianist

George “Bud” Matyi, a popular New

Orleans entertainer whose trademark song

was a rendition of the 70’s sailor hit

“Brandy.” He, as well as house pianist

David Stuart Gary, would perish in the

horrific blaze.

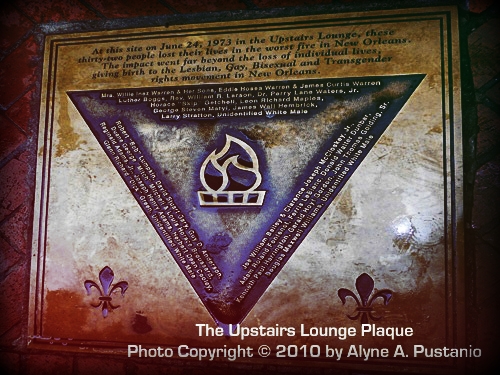

The Upstairs Lounge

Commerative Plaque ~ A Memorial Plaque

Fund

was set-up through the

Vieux Carre Metropolitan Community

Church.

Sitting with Jimmy

Massacci, Jr. in his second-floor corner

office on a humid, rainy June day, the

events of 37 years ago seem vividly

real.

“That window right

there,” says Massacci, pointing at the

window to my right, “that’s the window

where the man got stuck in the bars and

burned alive.” Immediately, images I

had seen of the charred corpse of MCC

Rev. William Larson, frozen in the

grisly pangs of death, come to mind. “I

think he was there all that next day,

while they were in here investigating.

Didn’t bother to cover him up or

anything.”

For Jimmy Massacci (James

Jr.) the Upstairs Lounge remains a

prominent and sobering memory of his

childhood. “I’ll never forget it,” he

says, shaking his head.

The Massacci family came

to New Orleans a generation ago when

James Massacci, Sr. agreed to take on

the job of managing and promoting famed

New Orleans trumpeter Al Hirt. “Little

Jimmy” was always at his father’s side

and the French Quarter soon became a

familiar stomping ground; it was a

natural progression when James Massacci

went into the bar business for himself

and in the early 70’s James and his wife

JoAnn opened the Jimani.

“Jimani? Gemini?” I

ask. “How do you pronounce it exactly?”

Jimmy laughs. “It’s a

combination of my parents’ names, my

mom’s idea – Jim And I, see?”

He continues, “Of course

a lot of what you see up here [in the

old lounge area] has changed a lot since

it was the Upstairs. We’ve had several

different businesses making changes over

time, but if you look around you’ll see

the original brick walls and especially

around the windows and at the top of the

ceilings, you still see the charred

bricks. And I’ve left a lot of the bars

in place,” he adds, “just to show what

they had to deal with to try to get out

that night.”

Looking around, I comment

on how horrific it must have been.

“I’ll never forget it as long as I

live,” he says. “I can tell you that.

“Those stairs you came up

from outside,” Massacci says, “well

those are the same stairs and the

outside door is the same. It was kept

locked. Whoever did it had to be a

regular and had to know the routine.

“They threw something all

over the stairs, probably lighter fluid,

and then they tossed in a Molotov

cocktail and the whole thing exploded.

But the people in the Upstairs wouldn’t

have known right away if they didn’t

hear the buzzer.” Massacci shakes his

head. “They opened that little panel

and it [flames] just shot into the room

like a big fireball.”

Beyond the Front Door: The Stairway

to The Upstairs Lounge photo

Copyright © 2010 by Alyne A.

Pustanio

That night, the dwindling

group of friends in the Upstairs lounge

gathered around the piano, as they had

so often, and sang a few choruses of

“United We Stand,” swaying together and

repeating the verses, happy in each

others’ company and celebrating the

remains of Pride Weekend. David Gary, a

pianist who played regularly in the

lounge of the new Marriott Hotel across

the street, was on the keyboards; soon

Bud Matyi would take his turn and round

out the evening.

At approximately 7:56

p.m. the buzzer sounded on the

downstairs door. This usually indicated

that a cab had arrived, but curiously no

one had called a cab. The single

second-floor door into the Upstairs

lounge was one of the old “Speakeasy”

kind with the little sliding panel set

at eye level so that patrons could check

out who was in the stairwell. Someone

went to the door and slid the speakeasy

panel back. Like a stream of napalm,

flames shot through the little hole into

the plush Upstairs interior. Velvet

curtains, silk panels, damask table

cloths, heavy stage curtains, carpets –

within minutes everything was consumed

in flames. The bar became an inferno.

Emergency exits were not

marked and the windows that weren’t

jammed with boards were covered with

iron bars. The two fire escapes

suspended on the sides of the buildings

hovered a full story above the street;

victims who made it to the fire escapes,

some of them in flames, had to jump the

full story to the street below,

receiving worse injuries as they did so.

A very few who were thin

enough, and frightened enough, managed

to squeeze through the iron bars at some

of the windows. Unfortunately, however,

when MCC Rev. William Larson attempted

to escape the same way he became wedged

in the bars and burned to death.

Witnesses gathered on the street

listened in helpless horror to his cries

of, “No! God, no! No!”

Larsen’s body would be

left there throughout the next day as

police and fire investigators plumbed

the scene. The sight was shown

endlessly on local television and even

made the front page of the local New

Orleans papers. Not a single person

thought to provide the pastor’s corpse

the decency of covering his remains.

When they arrived on the

scene, James Massacci and his son Jimmy

found the streets blocked off for

several blocks. Police vehicles and

fire trucks were lined up around the

building and groups of people were

standing around looking up and

pointing. The acrid smell of smoke, and

of something else that Jimmy couldn’t

identify at the time, filled the night

air.

James Massacci took his

son to a vacant lot across the street

from the bar near the Marriott and

admonished him to “stay right here”

while he [James] went over to the

smoldering remains of the building for a

closer look.

Jimmy Massacci watched as

his dad convened with police and

firemen; they, like the crowds nearby,

were looking and pointing. Jimmy

remembers a kind of excitement in the

air as local news crews arrived on the

scene and started filming or

interviewing onlookers. In the stark

klieg lights of the TV cameras, the

charred building and the strange objects

at the windows looked even more

surreal. But Jimmy was enthralled.

“Well, it went on into

the next day,” he continues his

account. “The police and firemen had to

investigate and then they had to remove

the bodies.”

Newspaper reports of the

time described bodies “stacked like

pancakes” at the exit doors, and firemen

“wading through charred flesh … some of

the bodies had been completely cooked.”

“It’s a smell I’LL never

forget,” Jimmy says, grimacing. “Burned

meat, or maybe old, rotten burned meat.

Just horrible. And they didn’t seem

like they were in any hurry to get the

bodies out of here.

“Of course my dad was

anxious about the whole thing,” he adds,

“because it was horrible but also he had

lost his business. The bar [he motions

downstairs to the Jimani] had so much

water damage it was almost a complete

loss. So he [James, Sr.] had lost his

livelihood and his investment. He could

have lost even more that night, but one

of his employees had the presence of

mind to go into the bar the next day and

get the cash box and the money from the

register and,” he hesitates, “this is

horrible but it really happened … When

the guy was coming out the front door of

the bar, the body that was in that

window [the pastor’s frozen burned

corpse] broke apart and fell on him!”

A stunted silence came

over us as the rain crackled on the

windows outside. Jimmy Massacci nods

his head. “That really happened.”

In addition to the

horribly incinerated Rev. Larson,

twenty-eight other individuals lost

their lives that night, and three others

later died of injuries received in the

fire. The death toll was the worst of

any fire in New Orleans history up to

that time, including the great fire of

1788 that burned the old French Quarter

to the ground. It was also the largest

mass murder of homosexuals ever in the

U.S. and what is more, it is a crime

that has never been solved.

But the city of New

Orleans did its level best to ignore the

whole event. The fire exposed a

surprisingly deep fissure of homophobia

in a city that has historically prided

itself on its egalitarianism and

cosmopolitan tolerance. For the first

time, New Orleans had to confront the

reality of a thriving homosexual

community in its midst. Evidently, this

was a very hard lesson for it to learn.

News coverage, both print

and television, made every effort to

omit the fact that the fire had anything

to do with homosexuals in the community,

even though a gay bar and members of a

gay church congregation had been

involved. The stories that appeared

included quotes from local citizens that

can only be described as ignorant, such

as a cab driver who said “I hoped the

fire burned their dresses off,” and one

woman who opined that “the Lord … cooked

them.” Local talk radio hosts were

making jokes such as, “What do they bury

the ashes of queers in?” The answer:

“Fruit jars.”

Statements from the local

police and fire chiefs, though less

caustic, were equally dismissive, with

NOPD chief detective Henry Morris

pointing out that identifying the

victims would be especially problematic

because “thieves hung out there [with

these people] … and you know it was a

queer bar.”

The story disappeared

from television and print news within a

few days.

For the victims, there

seemed no rest. Churches across the

city, churches of all faiths, refused to

allow services to be held for the dead,

and even forbade memorial prayer

meetings in their honor. The rector of

St. George’s Episcopal Church agreed to

allow a small prayer service on the

Monday evening following the event and

was promptly rebuked by his bishop.

Eventually, a local Unitarian church and

St. Mark’s United Methodist Church in

the French Quarter offered sanctuary for

those seeking to share their grief and

mourn the deaths.

City officials made

gargantuan efforts to completely ignore

the tragedy; no statements of any kind

were ever issued from the City

administration. Even more callous and

stunning, some families would not even

step forward to claim the bodies of

their dead sons, so rabid was their fear

of being vilified for acknowledging that

a child of theirs might have been gay.

Several anonymous individuals stepped

forward and paid for some burials, but

the unclaimed, the unwanted, were dumped

together in a mass grave in a Potter’s

Field on the outskirts of New Orleans,

buried alongside criminals, vagrants,

and departed pets.

“My father was a very

tolerant man,” Jimmy tells me as we

leave his office for a tour of the

building. “He was a man who said, ‘live

and let live,’ you know? It didn’t

matter to him if they were gay or

straight, he treated everyone the same

way.”

Then Jimmy laughs as he

remembers how his father used to get

annoyed with the noise from the Upstairs

dance floor. “You know what it was

like,” he laughs, “I mean it was the

‘70’s, you know, and everyone was

wearing those stupid clogs with the

wooden platform heels. Well, when

they’d get started up here dancing, and

with the music going, the sound of those

shoes just drove my dad nuts!” He

laughs, “That’s the only time he had to

come up here and tell them, ‘Alright!

Keep it down with those damn shoes!’”

Jimmy also shares a

little known fact about his father.

“After the fire, he was the only one who

put up a reward for the capture of

whoever did it. He felt awful about it

and put up his own money.”

Asked if they had any

leads, or if his dad had any suspicions

about who it might have been, Jimmy

shrugs, “Well, they caught a guy a day

or so after in a diner over on Royal

Street. He had been bragging that he

was the one who did it, but the police

finally said he was just some nut taking

credit for it, for ‘killing fags,’ so

they let him go.”

But Jimmy also gives a

knowing nod to my suggestion that rumors

are still rampant in the New Orleans gay

community. “Oh yeah,” he says,

“somebody, somewhere knows who did it.”

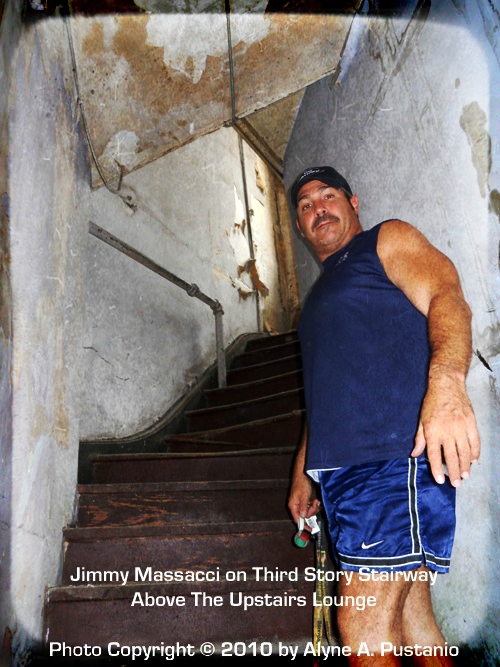

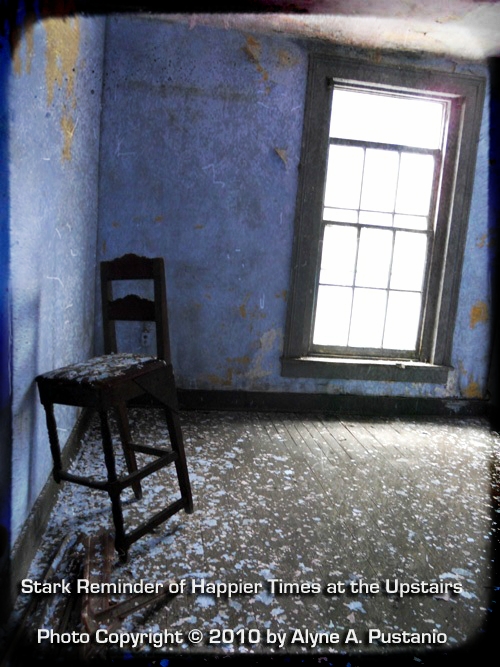

We tour the empty

portions of the second level – some

parts have been converted into a kitchen

serving food to Jimani customers below –

and then Jimmy takes me to the little

used third story, a section of the

building barely changed from the time of

the fire thirty-seven years ago.

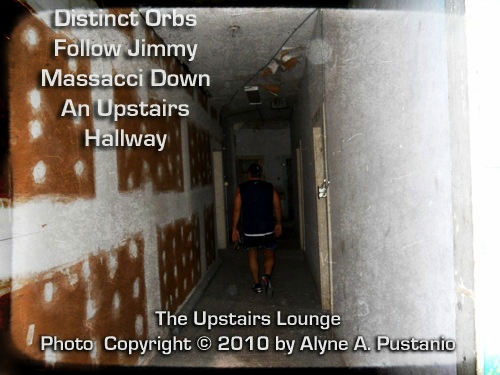

Digital camera images

reveal the presence of several possible

positive orbs and definite cold spots

are encountered here. These bare,

forlorn apartments, where the gays of

the Upstairs had carved out what little

intimate time they could in the

hit-and-miss sexscape of the early

1970’s, have a heavy atmosphere of

sadness. The rain tapping on the roof

adds to the gloom. I’m not unhappy as

we wrap up the tour and return to

Jimmy’s office.

When asked if he has ever

had any strange experiences in the

building, anything that he might

categorize as supernatural, at first

Jimmy shrugs. This doesn’t surprise

me. At 50, Jimmy Massacci is fit and

muscular; straightforward and

level-headed, I can tell he is not the

type of man that scares easily.

“Well, I hear things

every now and then, when I’m here late

or alone,” he admits, then his eyes

light up. “I will tell you this,

though: One afternoon I was here with a

friend of mine; the bar wasn’t open and

I had just stopped by, and as soon as we

came up here I thought I heard

something. I looked at my friend and he

nodded that he heard it, too.

“My first thought is,

‘Well, it’s a homeless person or

something,’ you know? Maybe a vagrant

got in, but just in case, I had my gun

with me. We both had flashlights and we

went off into the empty part [points

toward the little-used second story

area] and I could definitely hear

something by this time. You’re going to

laugh,” he says with a grin, “but it was

chains rattling.”

I do laugh. “That’s a

classic!”

“Yeah, but it was

definitely chains, because there’s an

old elevator in here from years ago, one

of those old crank kind with the big

wheel and the chains,” Jimmy replies.

“We don’t use it because it’s blocked

top and bottom and can’t go anywhere,

but the mechanism is all still there

from the days when this was a cotton

mill.

“So my friend and I go up

to where the chains and the wheel are

and we see that the old chains are

moving – they’re swinging back and

forth. I even asked my friend, ‘Is that

chain moving,’ and he’s already backing

up,” Jimmy laughs remembering his

friend’s reaction. “And then all of a

sudden, there’s this feeling of ice cold

air and I’m standing in it. And let me

tell you, it was hot like it is today,

and those rooms up there get unbearable

in the heat. That cold breeze came out

of nowhere, and it was blowing the

chains!”

Jimmy laughed and held up

his hands. “I said, ‘That’s it! We’re

out of here!’ I told it, ‘Everything’s

OK! We’re leaving right now!’ and we

hauled our asses downstairs and got the

hell out! THAT scared the hell out of

me!”

On the 30th

anniversary of the Upstairs Lounge fire

a plaque appeared on the sidewalk in

front of the door outside Jimmy

Massacci’s bar.

“I never knew anything

about it!” he says. “I was out of

town. I come back and there’s this

plaque there all of a sudden. I mean,

I’m glad it’s there, it should have been

put there a long time ago, but no one

even bothered to tell me about it, you

know?”

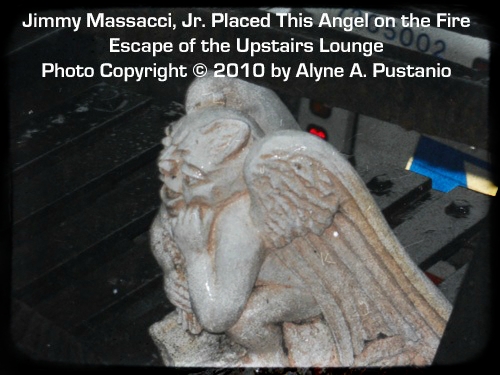

Jimmy naturally takes the

history of the Upstairs fire very

seriously and not the least because it

had a very dramatic and real effect on

his personal life.

“My dad never forgot

those people who died,” Jimmy said. “He

kept that reward out there for years,

but of course nobody ever came forward.

Another thing about my dad, that most

people didn’t know [James, Sr. has

passed on] is that he was always into

that esoteric stuff – he believed in

astrology and all that, and I think the

their spirits just are not at rest.”

When asked what he

thought might help the spirits to find

peace Jimmy minces no words, “I think

they need to be acknowledged and

remembered! I mean, there’s a huge gay

community in this city now and they have

Southern Decadence every year, and I can

tell you, there’s never a thought given

to the Upstairs and the men who died

there. I mean, those men died in part

so that the gay community could come out

and live and be what it is today. At

the very least, somebody ought to

acknowledge that."

THE

INVESTIGATION

In late June, close

to the 37th anniversary

of the Upstairs fire, Jimmy Massacci,

Jr. is providing exclusive,

all-access to the old Upstairs

Lounge and the remainder of his

building to members of LOUISIANA

STATE PARANORMAL RESEARCH SOCIETY

for the first-ever in-depth,

extended, professional paranormal

investigation of the premises.

LSPR-Society will be

searching for residual evidence of

the traumatic events, seeking

contact with souls still trapped

there, and gathering evidence in the

first leg of a quest to bring to the

UPSTAIRS and the MASSACCI family the

recognition, acknowledgement, and

validation they so richly deserve.

|